Check out the full big wall video course, or download the e-book.

What is Big Wall Climbing?

Big wall climbing is a guaranteed adventure. A big wall is essentially a vertical expanse of rock which is too big to climb in a single day. Food, water and other gear is taken up in a haul bag and nights are spent sleeping on a portaledge or natural rock ledge thousands of feet off the ground. Unless you’re a very good free climber, most routes require aid climbing to reach the summit.

Due to their length, steepness and complexity, big walls present a multitude of mental and physical challenges which you are unlikely to encounter in other disciplines of climbing. Easier big walls, such as the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome, are routinely climbed in a day by climbers with chalk bags instead of haul bags. Whereas obscure aid-intensive routes may take a highly experienced team over two weeks to complete.

Big walls aren't that common – the most famous, and accessible, is El Capitan in Yosemite, although there are many more in remote locations such as Baffin Island and Patagonia.

The Big Wall Climbing System – Overview

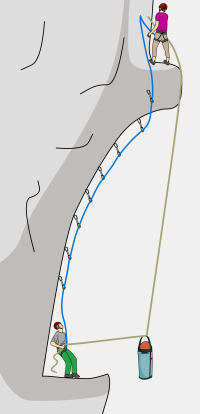

Leading

The leader ascends a pitch by aiding, free climbing, or both. They trail a haul line with them which is clipped to the back of their harness.

Belay Setup

At the end of the pitch, the leader sets up the belay and hauling system. The follower releases the haulbag from the lower belay and the leader begins pulling it up.

Hauling and Jumaring

Normally, the leader does not belay their partner up. Instead, they ‘fix’ the lead rope so the follower can ascend it.

The leader continues to haul the bag while their partner jumars up the fixed lead line, removing all the protection as they go. Once both climbers and the haul bag are at the top belay, the system can be repeated again.

What is Aid Climbing?

Aid climbing is the process of using gear to support your weight as you ascend. You attach fabric ladders (etriers) to gear and walk up them to gain height.

Conversely, free climbing is the term given to using your hands and feet to climb the rock and placing gear to protect from falling. This gear is not weighted unless you fall (you probably just call this ‘climbing’).

A knowledge of aid techniques allows you to climb routes which are way beyond your free climbing abilities. Aid climbing also has its own unique set of skills and problems that can be just as fun as free climbing. Beginner aid routes typically involve using the same trad protection (nuts, cams, etc..) that you’re already familiar with. More specialist aid gear (such as pitons and copperheads) is needed if you advance to harder routes.

Aid climbing is a useful skill to have even if you have no intention of climbing a big wall. Many alpine routes have sections that, in poor weather, may be impossible without using aid. Just a few aid moves may be all that is needed to reach a summit or a safer descent. Knowledge of aid techniques can also provide a way to safely move up or down a crag in an emergency.

Can I Climb a Big Wall?

Absolutely! The prospect of climbing a multi-day wall can be overwhelming, but when each part of the process is broken down into bite-size pieces, it becomes more of a realistic goal. Aid climbing, jumaring and hauling are all fairly straightforward skills to learn and well within the reach of any experienced trad climber. The important part is to go outside and practise (see Training). If you put the effort into getting these skills dialled, you’ll have a great experience on the wall.

Where Can I Climb a Big Wall?

With stable weather, simple approaches and plenty of easy routes, Yosemite Valley (California) is an excellent training ground to start your big wall career. Other beginner friendly places include Squamish (Canada), the Dolomites (Italy), Orco Valley (Italy), Catalonia (Spain) and Zion (USA).

Beyond that, big walls are spread across the world, often in wild and remote places which are expensive and difficult to get to, with extremes of weather and no rescue service. It is recommended to build up your big wall skills at easy venues first before you venture off to fulfil your wildest ambitions on a remote alpine big wall.

Choosing a Big Wall Climbing Partner

Choosing the right partner is probably the most important part of the climb. This decision can make the difference between having a great adventure or a total nightmare. The best wall partner is a person who you already know well, who’s company you enjoy, who shares the same goals and who you’ve climbed many multi-pitch routes with before.

Climbing a wall with a good friend will most likely be a fun adventure, whether you reach the top or not. Climbing with someone you just met on the internet is far less likely to work out well, regardless of their experience. You will be in close contact with each other for days; eating, sleeping and filling up poo bags immediately next to each other. It’ll make for a much better experience if you get along well.

How competent your partner is at big wall climbing should be a secondary consideration, since this is something that can easily be improved before the climb by training.

Choosing a Climb

Choose a route that you and your partner are excited about, a route that makes your stomach flutter when you think about it. You don’t necessarily need to be ready for it now – you only need to be ready when the time comes to climb it. Make sure to allow enough time to practise the techniques described in this book and be prepared to do an easier wall to ‘warm up’ first. Preparing for the adventure is part of the adventure.

Big Wall Climbing Etiquette

The rules on a big wall are very similar to those at any other crag. Generally, it all comes down to being polite, respecting other climbers and having common sense. Here are some basic etiquette guidelines:

- Don’t add extra bolts, rivets or bathook holes to existing routes (replacing old bolts and rivets is good though)

- Don’t chip holds or enhance placements

- Use clean aid where possible

- If other climbers arrive at a route before you, they get to climb first

- If you’re moving slow, it is polite to allow faster teams to pass

- Take your litter and human waste home

Training

To train for a trad or sport climb, you typically need to focus on improving your strength. However to train for a big wall, you need to focus on practising aid techniques and rope systems. Forget about climbing harder grades in the gym – that will make little difference. It doesn’t matter how good you are at other disciplines of climbing, big walling is a whole different game. It helps to be competent at leading 5.9 (HVS for the Brits), but climbing harder than that is not necessary.

Your first big wall begins by making a training plan which is focused on practising the techniques described in this book. Plenty of practise is essential. Skills such as hauling and jumaring are strenuous, slow and clunky at first, but with practise you’ll develop a smooth technique and then it becomes much easier. You should aim to reach a level of competence where you can set up any system without needing to refer back to this book.

However you choose to practise, always go with a partner and always back up any system which you are not familiar with.

The following checklist should be completed before attempting any big wall. Review what worked and what didn’t work during each session and focus on improving the things you found most difficult. This list assumes that you are already competent at multi-pitch trad climbing and self-rescue techniques. As with anything worthwhile, it will take time to build up a good level of competence. Trying to shortcut this process is extremely dangerous and will probably result in disaster.

After you and your partner have become fully competent at all the skills listed, you can try a short wall (e.g: South Face of Washington Column or West Face of The Leaning Tower). Once you have climbed a few shorter walls, you can move on to a bigger objective (e.g: The Nose or Salathe on El Capitan). With the competence gained from training and the experience gained on shorter walls, you’ll not only reach the top safely and efficiently, but also have a great time doing so!

Checklist

Placing all types of regular trad gear

Using cam hooks and skyhooks

Bounce testing

French-freeing

Leading a straight-up aid pitch

Leading an overhang

Leading a traverse

Passing gear between the belayer and leader during a pitch

Leading a pendulum

Switching between aid and free climbing during a pitch

Leading a tension traverse

Fixing mid-pitch

Setting up the belay

Releasing haulbags on a straight up pitch

Releasing haulbags on a traverse

Belay transitions

Cleaning a straight up aid pitch

Cleaning an overhang

Cleaning a traverse

Lowering out from a pendulum point

Jumaring a free-hanging rope

Packing a haulbag

Docking a haulbag

1:1 hauling

2:1 hauling

3:1 hauling

Space hauling

Hauling past a knot

Hauling low-angled terrain

Descending with a heavy load

Descending with a heavy load past a knot

Lowering haulbags

Lowering haulbags past a knot

Abseiling with a damaged rope

Descending low-angled terrain

Retreating mid-pitch

Setting up the bivi

Setting up a portaledge and fly (if applicable)

Using a hanging stove (if applicable)

Note

If you plan to fix pitches, short fix, climb as a team of three or climb a route requiring pitons, copperheads or a bolt kit, you’ll obviously need to practise those skills too.

How To Practise Aid Climbing

Top Rope

Many of the skills can be safely practised with a top rope. This could be done inside at the gym or outside at a single pitch crag. Stay away from popular routes and ideally choose a crag with crack climbs that are easy to protect.

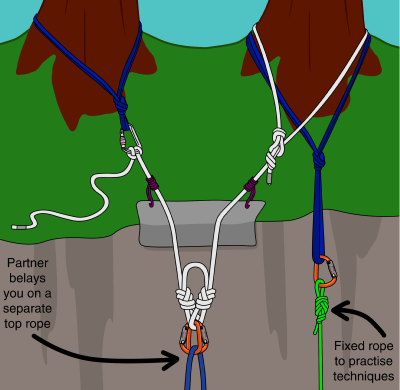

By setting up a top rope and a fixed rope as shown, you can safely practise placing gear, jumaring, cleaning gear, hauling and descending. With a sensible top rope setup, pendulums and lower-outs can be practised safely too. Progress to leading without a top rope back-up once you are confident moving up your aiders and testing gear.

Rock Angle

Try setting up top ropes on different angles of rock. An angle which is vertical or slightly lower than vertical is a good starting point. Progress to steeper rock and overhangs after that. Leading and cleaning are more difficult on steeper ground and require a modified technique. You’ll need to practise them both.

Jumaring

Practise jumaring down ropes as well as up them. This helps you develop a good thumb-catch technique.

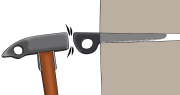

Hooks and Pitons

Stay away from established routes when practising placing hooks, copperheads or pitons. These types of gear can permanently damage the rock. Find a worthless lump of nonclimbable rock instead. If practising at ground level, bring a bouldering pad so you don’t hurt yourself if a piece blows unexpectedly. Aid-bouldering may not be the most fashionable form of climbing, but it’s a great way to learn the art of hooking and piton craft.

Hauling

Start by hauling a light load to figure out the system and then progressively add more weight each time. Fill your haulbag with water bottles or rocks. Pad the inside of your haulbag well if using rocks (a few layers of cardboard or an old piece of carpet) so you don’t wear holes in it before even climbing a wall.

Time

Time how long it takes to lead, clean and haul a pitch of similar length and difficulty to your chosen route. Remember to factor in time spent on belay changeovers too. Keep practising to improve your time and use this as a basis for calculating how long each pitch will take on the wall.

Multi-Pitch

Once you’ve built up an understanding of big wall systems on single pitches, you can progress to a multi-pitch crack climb. Aid climb the crack (even if you could easily free climb it), set up a belay and practise your belay transition and organisation. Take a haulbag and a portaledge too. It’s much more difficult to set up a portaledge when hanging on the wall than it is when standing on the ground. Cook a meal in your hanging stove, spend the night up there and climb a pitch in the dark if you want a full simulation of life on the wall. A two-pitch climb can be done with a night’s sleep halfway and you’ll still be back down in time for work in the morning. Don’t forget your poop tube!