I rolled from side to side for most of the night, peering through the gaps, waiting for morning. Outside, the Paine towers dominated everything; the landscape, my thoughts, my dreams.

My climbing partner, Callum Coldwell-Storry, and I had found shelter in a small, coffin-like cave beneath the towers, formed by a fallen house-sized rock. The line of The South African Route rose above, following a clean-cut corner system up the east face of The Central Tower.

The last guys to climb it (Nicolas Favresse, Sean Villanueva and Ben Ditto) had free-climbed the entire 1200-metre route. They were real climbers. We were average Joes. They can climb 5.14. I struggled with 5.9. To compensate, we came equipped with aid-climbing gear to hook our way through the hard pitches.

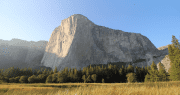

The Central Tower was wedged, shoulder-to-shoulder, between its two brothers; The North and South Towers. The triplets, each of them twice the height of The Empire State Building, were still growing and had an angry adolescent attitude.

The three sheer rock walls disappeared into clouds and then reappeared higher up, soaring majestically into the endless, windswept skies above, exuding a powerful dignity that was both tantalizing and terrifying at the same time. The mere sight of them was enough to turn courage into fear, excitement into anxiety, trust into suspicion.

Standing there, gaping at the turbulent expanse of granite and ice and cloud and sky, I felt a ridiculous greed and possessiveness come over me. I wanted to climb it all. I wanted us to have it all to ourselves. Sounds insane, but at least there were no other humans to dispute possession with us.

Our equipment and food weighed 180kg; the same weight as an average 500cc motorbike. We had hitch-hiked to the end of the road and, for seven days, shuttled our burden along tourist trails, through boulder fields and finally across glaciers to reach the base. The Central Tower, as grey as a dark secret, had something sinister to tell us.

In the coffin-cave, drips of water splashed on my face.

The blue dark of night was broken by the outline of a serrated summit ridge like the upturned spine of a stupendous primeval beast.

Below the crest, a wall of pale granite plummeted over a kilometre down to a permanent glacier and a wind-worried lake; a splendour of aquamarine, crested with small, white-topped waves.

I felt like a soldier trying to sleep in the trenches the night before a major battle. That wasn't so far off. Climbing the Central Tower is like going to war. The only way to succeed at a climb like that, I later learned, is either to be oblivious to the dangers, or to genuinely not care if you die in pursuit of the summit. At the time, I think Callum and I fell into both categories.

As with any war, you have to ready yourself for battle. We had patrolled the rainy streets of the local town, Puerto Natales, weaving through the bustle and competing with stray dogs to search bins and the edges of west-facing buildings where windblown rubbish tends to collect. In these places we found a sufficient supply of plastic water bottles for the climb.

We later collected seventy five litres of water in these odd-sized bottles from a small glassy flow which trickled from the glacier below the towers, making our bags weigh more than a family of lions. We had a portaledge to sleep on and an old wind proof cover to wrap around it. We were well prepared and that should have comforted us a little. But it didn't. Not at all.

A pink cloudburst detonated across the pale grey stone, quickly draining down to iridescent red. Tendrils of high cloud built in the morning sky. Callum was chewing his thumbnail.

"Ready?" He asked. The uncharacteristic doubt that emanated from the single word of his question greatly concerned me. The most fearless man I had ever met was scared of the climb we were about to do.

"Yeah, sure." In truth, I wasn't ready. I was frozen with fear; a fear of what I wouldn't find if I didn't go.

Terrific updraughts assisted our progress on the lower section of the tower, often giving us a feeling of weightlessness. The enormous tower soon developed an angry pugnacity in its attitude towards us, as if we were a parasitic itch on its coarse skin.

As we climbed the lower slabs, I noticed many deep scars on the rock; evidence that we were climbing through a regular rock fall area. Callum caught a glance of the scars. His gaze lifted and our eyes met. There was a genuine, exhaustive terror in the white-rimmed bulge of his eyes that I'd never seen before. I gave a solemn nod of understanding. The deepest anxiety emerged in the presence of the quiet air between us.

We continued climbing in trepidation, certain that every noise we heard was rock-fall. We sneaked through the lower slabs without being hit by falling rocks and began to build up courage on that first day.

But it was a cruel kind of courage that led us deeper into the mountain's clutches.

“What’s Spanish for tuna?” A foul odour emitted from the small tin.

“Atun, I think.” Callum replied.

“This doesn’t say Atun anywhere on it.” I forced a spoonful of the oily grey substance down my throat. “It tastes like vomit.”

“Huh. Maybe this pasta will dull the flavour a bit.” He emptied a bag of one-inch long, straw-like yellow strands into the stove and stirred it with a broken plastic spoon. The bubbling sound of the stove was muffled by fierce south-westerly tempests pounding on our portaledge cover. Snow melted and dripped through into our sleeping bags.

“I think I figured out why the pasta was so cheap.”

“Why?”

“Because it’s not pasta. It just dissolves and turns to glue.”

“What is it then?”

“I’ve no idea. Everything’s written in Spanish. I wish I’d listened at school.” He tsk'ed his tongue and sighed.

Windswept snowflakes were posted through holes in our shelter, adding a pleasant winter seasoning to the lumpy grey gloop. Whatever that sludge was, we ate it every day.

CCCRACK! A thunderous clatter forced us awake. The deafening sound reverberated through the cold morning air.

CCCRACK... BOOM! Our portaledge shook with a violent tremor.

"What's going on!?" I yelled.

"What!?" Callum slid out of his sleeping bag with a frantic wriggle. "Storm?"

CCCRACK!

I ripped open our portaledge cover. I couldn't believe what I saw.

Directly across from us, hundreds of metres of rock was falling off. It crashed down the rock face, annihilating everything in its path. It was like watching a 20-storey building collapse, while sat in the next building.

BOOOOOM! The huge rock exploded into the glacier below. Enormous chunks of ice and rock were spat from the impact zone, tumbling into crevasses and destroying their own paths.

The event had doubtless been in preparation for hundreds or thousands of years – snow falling, melting, trickling into minute fissures, dissolving the cements that bind granite particles together, freezing and expanding, slowly wedging the rock from the main face.

The tower creaked and groaned as smaller rocks followed their powerful leader. An immense dust cloud erupted in slow motion. I shivered. I didn't know what to say.

An eerie jacket of calm cloaked the towers. The sky was curdled grey, saturated with lumps of cloud. It looked like a giant plate of our tuna-pasta disaster. Dusty air encroached upwards, engulfing us in the burnt cordite scent of fresh rockfall.

A lone nylon sling flapped in the faint breeze, creating the only noise in an otherwise silent atmosphere. I'd never seen a falling rock bigger than a golf ball before.

“That would have landed on us if we’d started the climb today.” Callum said, monotone and matter-of-fact. He had bags under his eyes.

“What should we do?”

“Don’t know.”

Dust particles swirled around us, exaggerating the apocalyptic scene. Hours later, when the dust had settled, we saw the rubble and destruction. The glacier that we walked across had been obliterated. Car-sized rocks covered our footprints.

“It’s probably safer to go up.” Callum said. Despite the cold, sweat streamed from his brow. He looked older, like he was ageing a year for each pitch climbed.

I nodded. We escaped unscathed that time, but the malicious tower had other cruel intentions for us.

We continued battling relentless winds and dodging falling rocks, while inching our way up the enormous vertical wasteland, driven by the fact that we could only be rescued by ourselves.

It became commonplace to see blocks the size of car wheels arcing out into space, followed by the familiar echo of a dull explosion as they hit the lower slabs. The days blew by, merging into a wicked blur of cut ropes, rockfall and bad food.

On our 8th day we reached a point which became our 'high camp'; the top of a huge dihedral: an alien refuge of smooth, solid rock amidst a vast citadel of choss.

When we climbed from there, we fixed our tattered ropes as far up as they would go, meaning we could quickly ascend them to make a push for the summit when the weather granted us permission.

On the morning of our 10th day we woke to find an extremely rare, perfectly cloudless, purple-blue sky; the lake below tranquil and still, the air charged with silence and frost, the only movement the arc of the occasional blue eagle gliding by.

Frost thinly glazed the glacier's surface, until it beamed in the burnt-red eastern light like polished marble. The Towers, largely hidden by gloom for the past ten days, stood out in their aged and mighty splendour.

The ropes above us had frozen into windswept positions and were encased in icicles. Fortunately, the ropes' icy jackets added a necessary layer of protection against the countless sharp edges of rock they'd been blowing over throughout their time up there.

We ascended our ropes and crept through a vertical maze of caravan-sized blocks balanced precariously one upon the other like a teetering staircase of giant Jenga towers. The euphoric rush of summit glory buzzed between us.

The landscape below resolved into a quilt of glacial white and pale grey rock, punctuated by the emerald green lake.

The Andes mountain range stretched into distant horizons to the north, west and south, a view that had been hidden from us as we climbed the east facing wall. Seemingly endless black and jagged peaks poked out above a thick snowy blanket, all with peace and strength and freedom. The mountains seemed to rise infinitely into a world beyond the world. It appeared to be the end of the earth, or perhaps the beginning of another earth.

In the west, a thin film of cirrocumulus softened distant mountain peaks. We sat on the very tip of the tower, absorbing it all on a small block that had persevered through millennia of winter's ice and vicious winds. Callum's white teeth gleamed through a grubby patchwork of beard and dirt. For both of us, a life-long dream had been completed.

After so much time away, the thought of civilization was unreal, unbelievable. The sun gave its parting kiss to the towers' summits, and golden light reverberated through the open space.

The setting sun gave the trio a brief but colossal spiky shadow which stretched eastwards over rolling hills until their summits touched the far horizon.

Dusk rolled in like a sea of phosphorescence. Our exhilaration intensified. We shook hands and posed for photographs. A happy and excited grin spanned my rosy cheeks; an expression which had brightened my face every day for as long as I could remember.

The next time I smiled so unabashed like that was six months later.

Tufts of clouds drifted overhead. Cold, hostile weather had caught up to us. Sleet stung my face. The wind whipped it under the collar and sleeves of my jacket. The mist was so thick that visibility was down to a few metres.

Callum's mouth was moving erratically. He was shouting something but his words were snatched away by hurricane force winds before they could reach my ears.

He was losing battle with sixty metres of rope which was blowing directly upwards, whipping over sharp edges of loose rock.

Getting down was not an option until the wind eased. The strain of the past days had turned his skin a chalky white, accentuated by his dark jacket. An almost detached expression was settling into the eyes of a man who could suffer more than a Chilean street dog. Our portaledge clattered against the rough granite wall; a broken sail on a sinking ship.

On the third day of the brutal storm, the wind softened enough for us to pack away our shelter and continue our battle down the remaining nine hundred metres of vertical rock.

We made each abseil anchor far to the side of the previous one, to avoid being hit by rocks when pulling our ropes. This technique proved to be extremely valuable, especially on the lower slabs. After more than twenty abseils, but still with a few more to go, strong winds had blown our ropes onto a ledge about twenty metres directly above us.

Cautiously, we pulled them through. Small pebbles fell and bounced off our helmets as the rope snaked through rock obstacles high above on the ledge.

Suddenly, a booming groan echoed from deep within the tower. On the ledge above us I saw the image that - even years later as I write this - continues to haunt me when I close my eyes. An enormous jagged rock slid over loose pebbles to the end of the ledge.

In slow motion it turned to look at us with revengeful eyes, angry that we had awakened it from a thousand year sleep.

“No!” Callum cried in the despondent tone of a trapped animal. His eyes and mouth stretched wide into ovals of disbelief and horror as the rock tumbled from the ledge and rapidly accelerated directly towards us. “Oh fuck, it’s coming straight for us!”

Pinned in close to the wall with no escape, the only thing we could do was watch and hope. The air above us ripped into a deafening, scraping scream.

And then, silence.

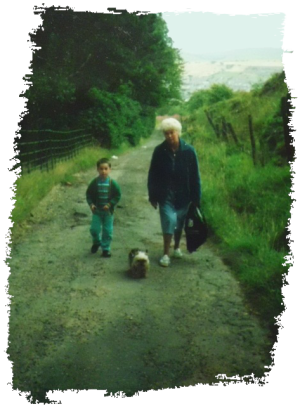

I'm splashing through muddy puddles in a woodland park on a foggy summer’s morning. The scent of moist vegetation fills my lungs. At the age of five, I'm thrilled to be guiding my grandma and her small brown dog, Toby, through the new and exciting land.

I stretched back and threw my hands up in an attempt to deflect the giant rock, but its overwhelming dominance crumpled my shaky arms.

Toby, strong for his old age, runs ahead of me. The long hair from his abdomen collects mud from the damp path.

In one movement, the violent rock crushed the breath from my chest and slammed into my right leg. A plume of warm air visibly escaped into the cold air around us.

Toby's droopy ears flop in rhythm with his short legs as he runs.

The rock erupted into a shatter of vehement thunder against the slabs below. I opened my mouth. I opened it so wide my jaws creaked. My lungs tightened, squeezed. It was like breathing through a drinking straw.

Without stopping, Toby turns around and smiles with his slender, drooling tongue and wide, excited eyes, beckoning me to follow him.

Numb with a bursting surge of adrenaline, the only pain I could feel was a tingle of horror creeping across my skin.

I try my best to catch up with Toby. The hood of my jacket bounces on my back as I run. He disappears out of sight. My grandma shouts me, "Come back, Neil. Come back." The tone of her voice is worried and serious.

I darted a glance at my leg to check if it had been severed or not. But that was the least of our worries.

“You okay?!” A voice shouted. It had the desperate edge of someone in real peril. The words echoed distantly through my confused mind. My hearing was muffled, my vision blurred.

Am I alive and dreaming, or dead and remembering? I wondered.

“You okay?!” The voice repeated.

“Ummmm I... I dunno.” I forced out shaky words.

“Oh fuck! Look at that! Don’t move!” The voice screamed.

The rock-fall had almost completely stripped our belay from the wall. All of our haulbags, all of our equipment, my life and the life of my best friend were dangling solely from a single strand of frayed cord, the thickness and strength of a shoelace, which was wrapped around an ancient, rusty piton.

Our lives were literally hanging by a thread.

All laws of physics state that the thread should have snapped. I'll never know how it didn't.

It is moments like this that bring out our true character; moments that are simultaneously the worst and most memorable of our lives. When our lives are hanging from a thread, there is nothing to hide behind. This is when we discover who we really are.

Callum slotted a small nut in a crack just above us. His fingers were trembling. The nut didn't fit.

I couldn't move. I couldn't blink. I couldn't take my eyes off the straining thread and rusty piton which our lives were hanging from.

He tried again. A cold, slate-grey flush of shock bleached his face. I watched the old piton flex with each gentle movement. The nut wouldn't fit. Nothing would fit.

The shoelace-cord creaked. My stomach roiled with nausea. If Callum was as hopeless as me, we would have dangled there until the thread snapped, perhaps a few minutes later. But there was a fighting strength within him. A strength to fight to the very end.

With incredible care and precision, he smeared his foot on a dimple in the rock and reached higher. He placed a small cam, and clipped me to it.

Then clipped himself to it.

We were safe once again, safe enough. But the fact is that we should have been swept from the rock and swallowed by the deep crevasses of the icy coffin below.

The adrenaline began to subside, intense pain roared through the veins in my leg. My eyes rolled around in erratic swirls, as if what they had just witnessed was beyond the realm of reality and they were searching the depths of my mind, hoping to find a less hellish nightmare.

I tried to speak but the fuzzy onset of unconsciousness had frozen my voice into a hard lump of wordless desperation in my throat. All three of our ropes were shredded to the point of uselessness.

The rest of the descent is a distant blur in my memory.

Spikes of pain battered my leg for every step of the four-day walk back. It healed soon after but the emotional scars took much longer to heal.

I once moved to the other side of the world because I'd fallen in love with a woman. Shortly after, she cheated on me. It's the same pain.

Six tough months passed before I tied into a rope again. But when I did, the vibrancy of life returned. Trust was rebuilt. My psyche for everything came flooding back. Life was exhilarating again.

I'll never stop climbing.