This article is part of the book - Trad Climbing Basics.

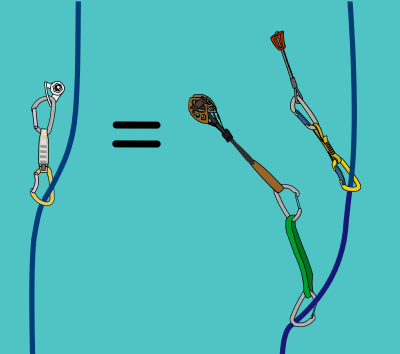

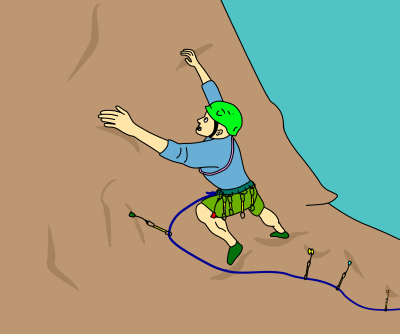

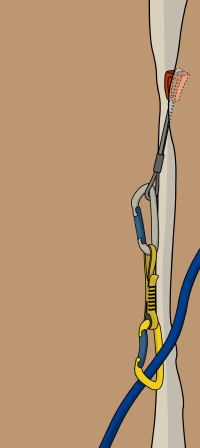

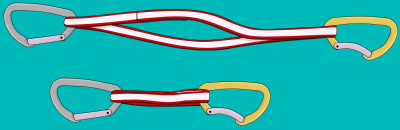

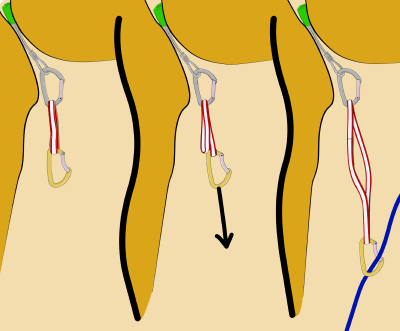

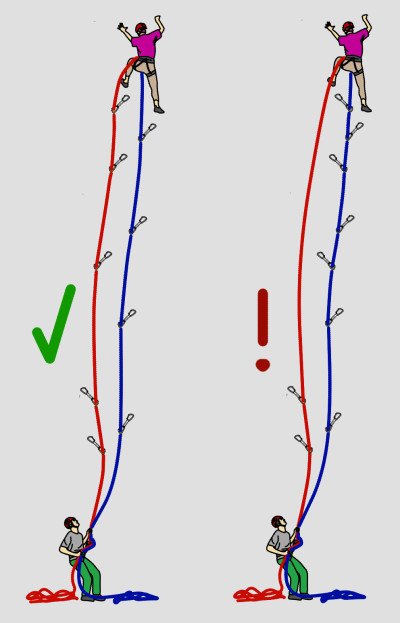

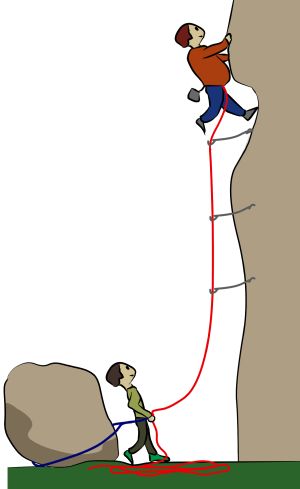

When climbing indoors, or at a ‘sport’ crag, the leader clips their rope, via quickdraws, into pre-existing bolts.

On a bolted route, it is generally safe to fall at any time. Having this high level of safety allows the leader to focus on the physical aspect of climbing up the rock.

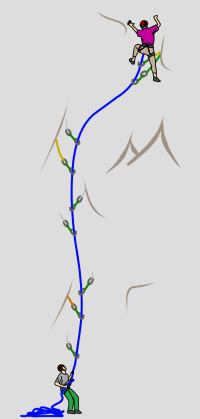

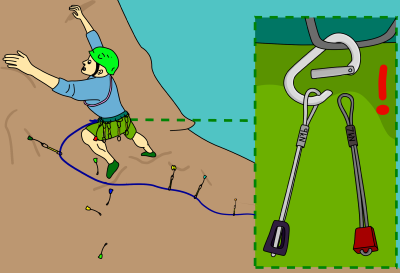

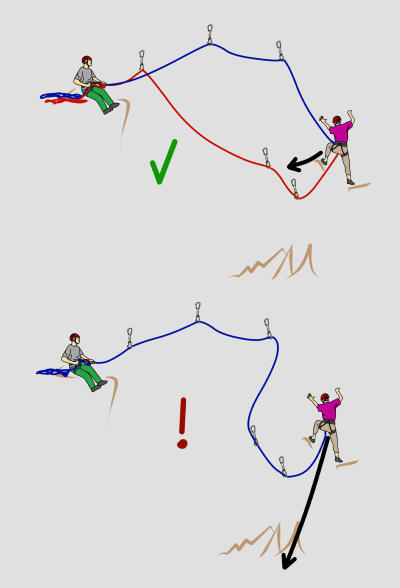

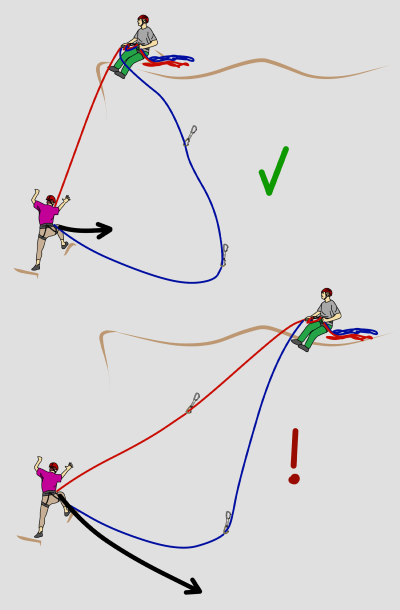

When trad climbing, the leader must place their own gear in the rock.

To be safe when trad climbing, the leader must focus on finding gear placements and then select the right piece of gear to fit. This adds a technical and mental aspect to the route.

With a good understanding of trad climbing skills, you can branch out from the indoor walls and sport crags to reach unique places that would otherwise be inaccessible.

Can I Trad Climb?

Yes!

Learning to trad climb is similar to learning to drive a car. It takes time, effort and commitment. It can be dangerous if you don't know what you're doing, or very safe once you become competent.

The articles on this website focus on the physics behind trad gear and the reasons for using different rope techniques. This is so you understand why each technique is used, and therefore you'll be able to adapt them for any situation.

So, learn the skills and practise them safely. Start with small adventures to build up your problem solving ability before you move on to anything bigger. And remember to have fun!

Trad Climbing Etiquette

There are different rules when you venture outside of the climbing gym. When you go to a new climbing venue, ask the locals what the special considerations are.

Generally, it all comes down to being polite, respecting other climbers and having common sense. Here are some basic etiquette guidelines:

- Avoid making excessive noise

- Keep your stuff in a small, tidy pile

- Take your litter and human waste home

- Stick to recognized trails to avoid trampling vegetation

- Keep pets on a leash or leave them at home

- Don’t alter the natural environment (never chip holds)

- If other climbers arrive at a route before you, they get to climb first

- If you’re moving slow on a multi-pitch, it is polite to allow faster teams to pass if you have plenty of time and there is no danger of rockfall – but you have every right to say no

Finding a Trad Climbing Partner

There are a few different ways to find a climbing partner, including:

- At the indoor climbing gym

- On a climbing course

- At a climbing club

- Through friends

- On internet forums

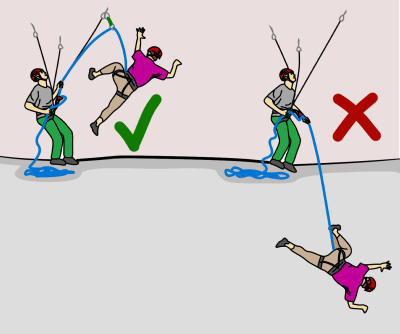

However you find a partner, it’s important to assess how safe they are.

A good ‘first date’ is to climb at the gym. Be upfront and honest about your skills but be aware that some people will exaggerate their abilities in order to impress.

If you are unsure of their abilities, have a staff member test you both on belaying and lead skills before you climb together.

Progress to a single pitch crag after the gym. Inspect the quality of their equipment and their anchor building techniques carefully before you move on to more committing multi-pitch routes.

Don’t blindly trust someone with your life until they have proven themselves trustworthy. Stop climbing with someone who does strange or dangerous things. Instead, recommend that they take a course, or read this manual, or both.

Route Finding

Some trad routes follow straightforward crack systems, and others weave an intricate path through a labyrinth of small features.

It is wise to scope complex routes during the approach and match the features you see with the guidebook description. Plan the descent too. Even if the main route is obvious, the handholds, footholds and gear placements (micro route finding) may not be so clear.

On popular routes, the clues are:

- Chalked handholds

- Polished footholds

- Lichen and dirt free rock

- Difficulty which matches the grade given

Be careful about continuing if you are off-route. It is usually better to downclimb to the last point when you were definitely on-route and reassess from there.

Your First Trad Climbing Lead

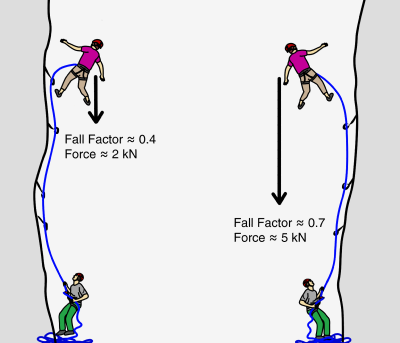

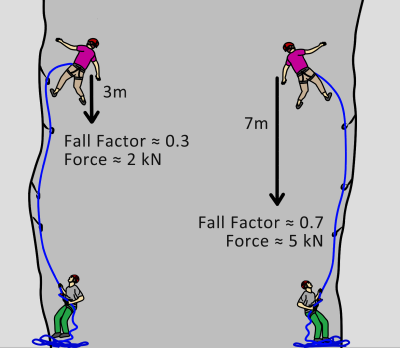

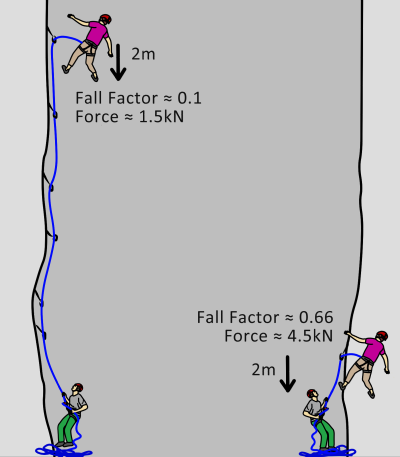

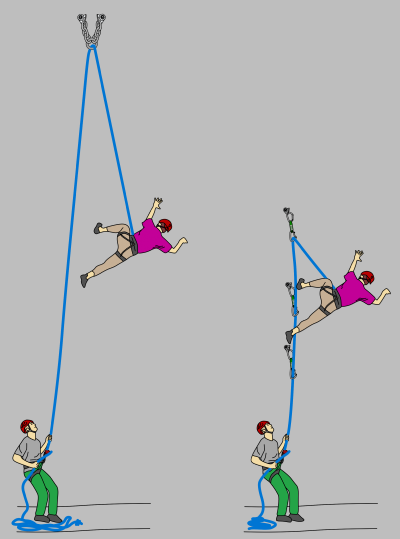

Leading trad for the first time can be pretty scary. Suddenly you're exposed to greater dangers than you would leading a sport route, or following a trad route. Here are some tips for your first few times on 'the sharp end':

Practise Placing Gear

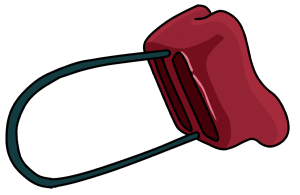

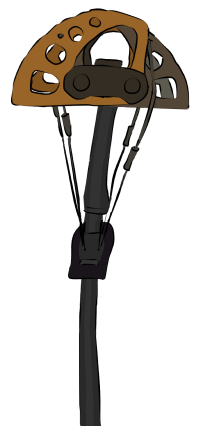

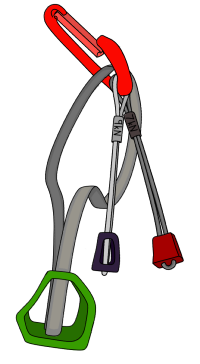

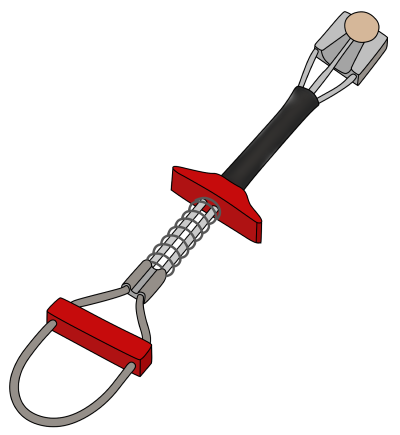

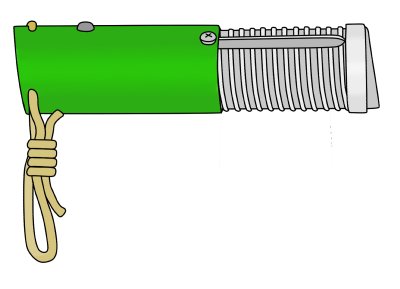

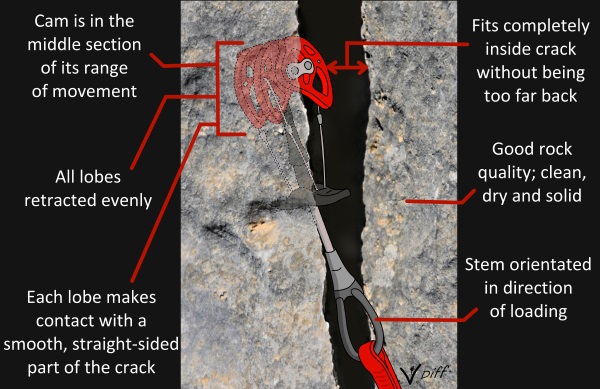

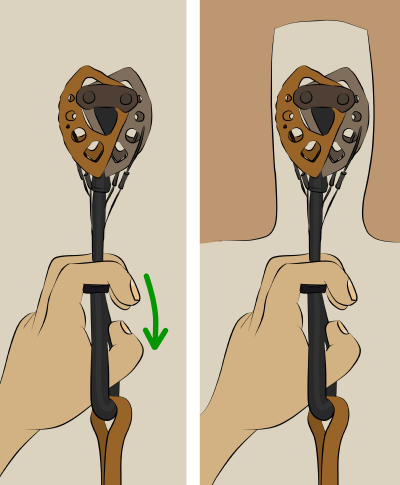

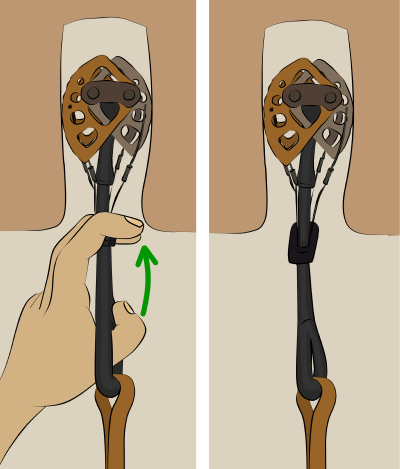

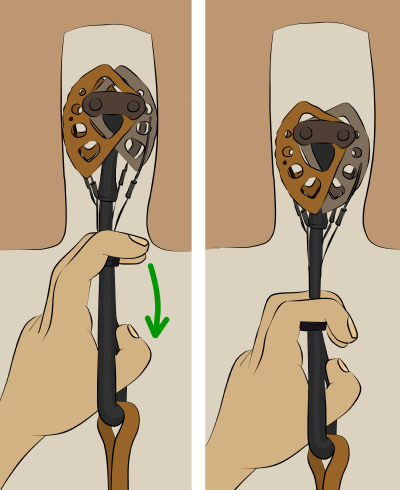

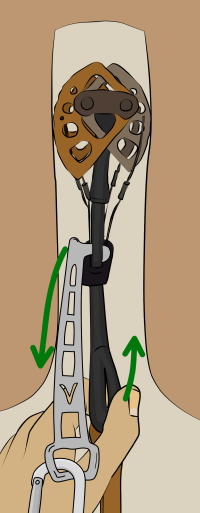

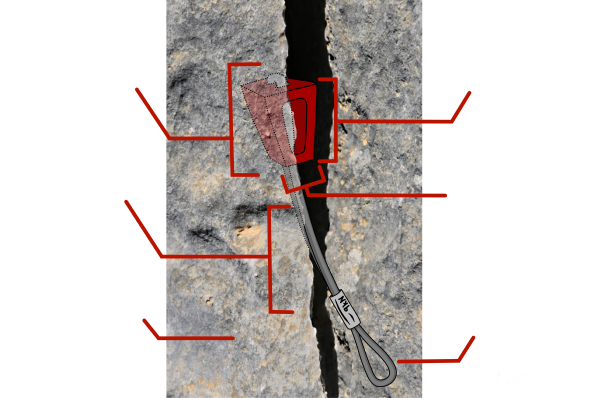

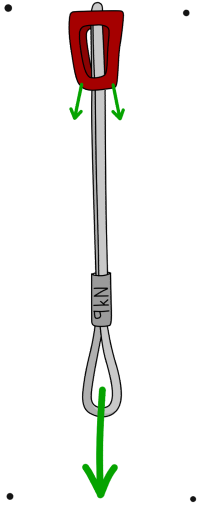

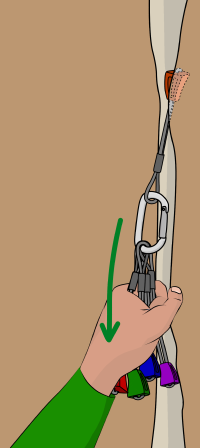

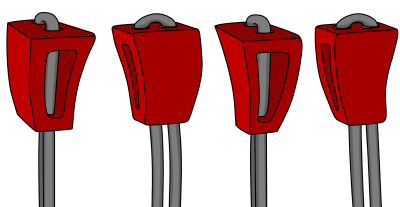

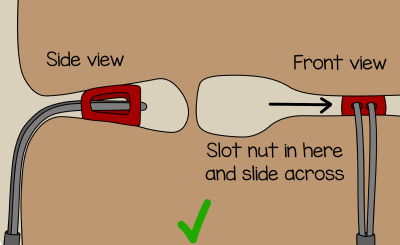

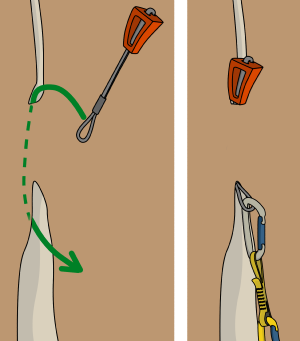

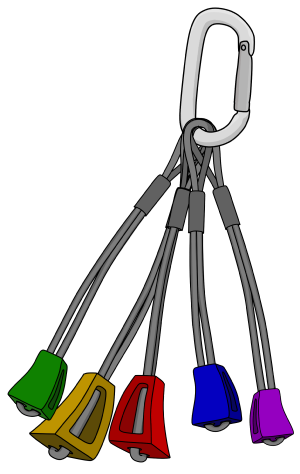

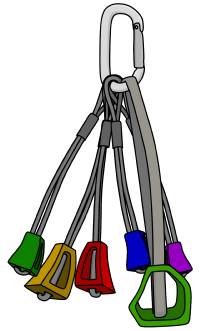

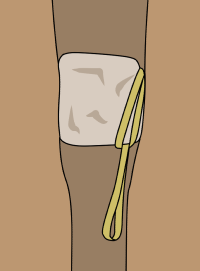

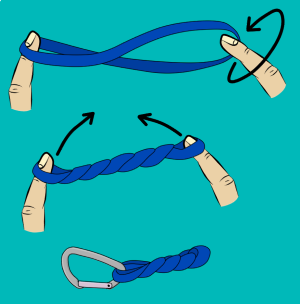

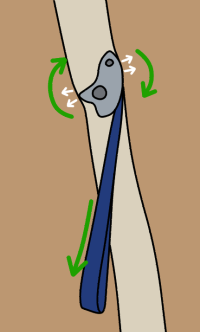

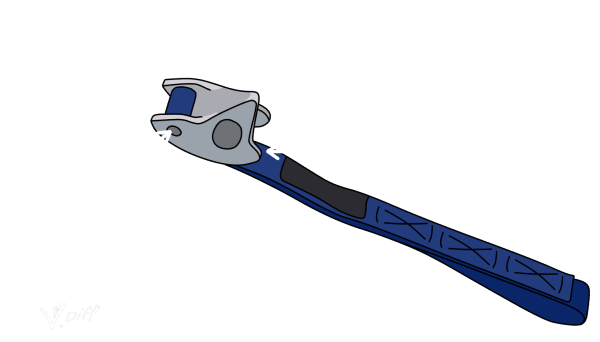

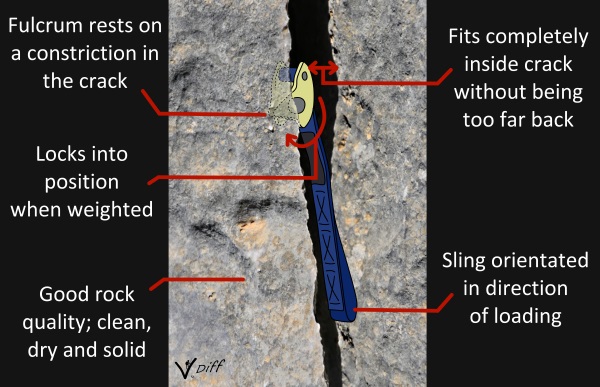

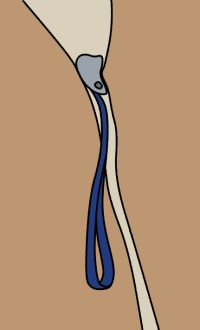

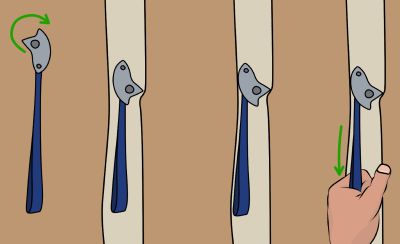

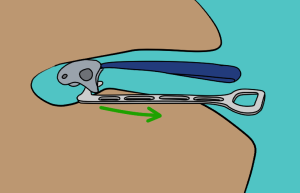

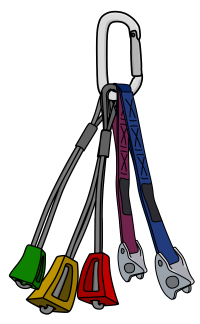

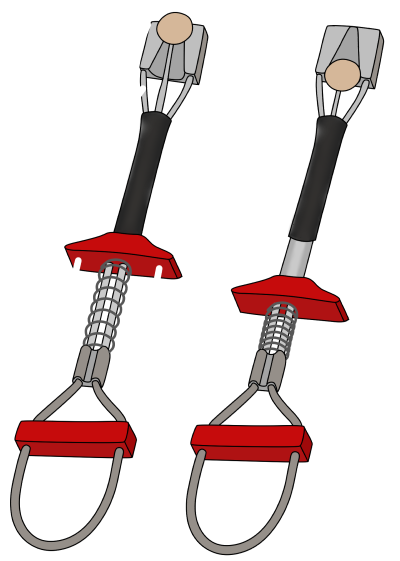

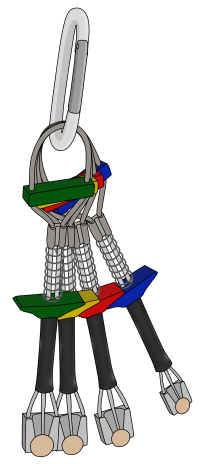

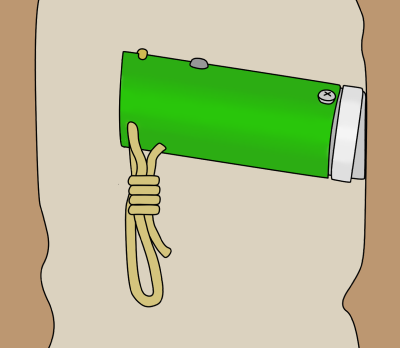

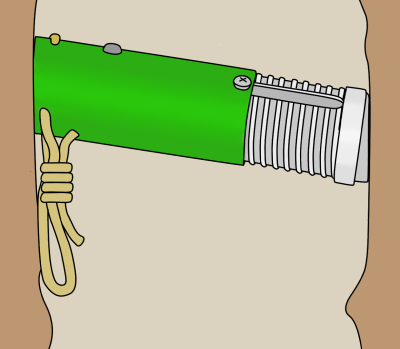

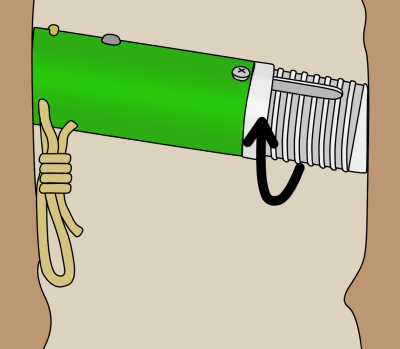

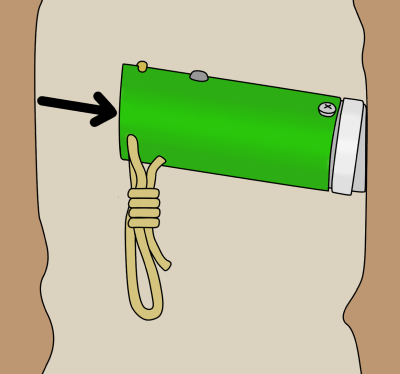

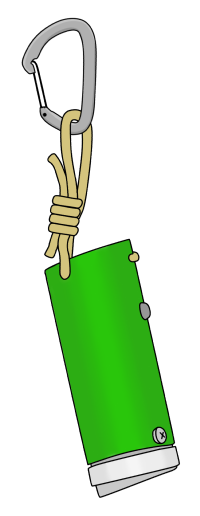

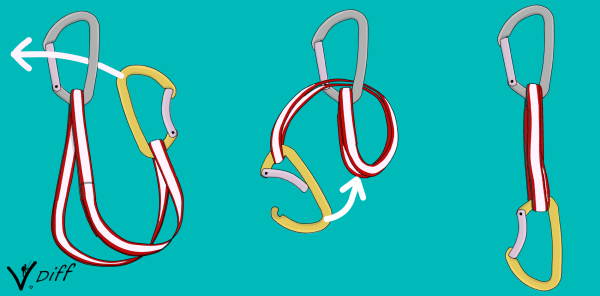

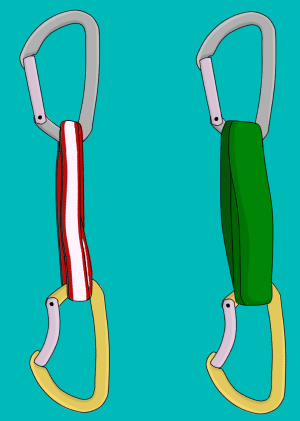

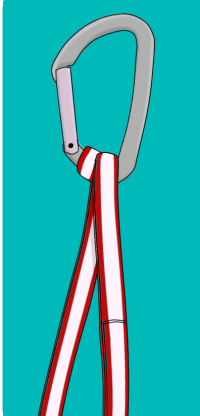

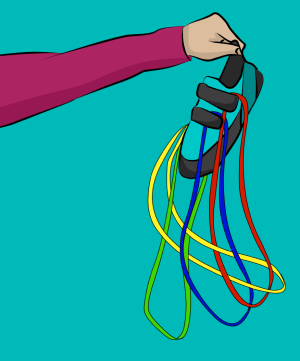

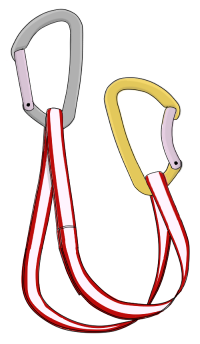

It is important to learn how to place trad gear well before you lead anything. A good way to start is to walk along the base of your local crag and place every piece on your rack in as many different spots as you can find. Get used to placing and removing each size and type of gear.

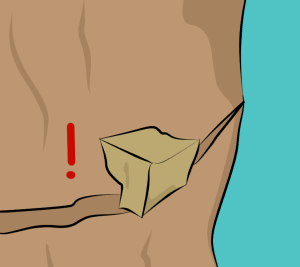

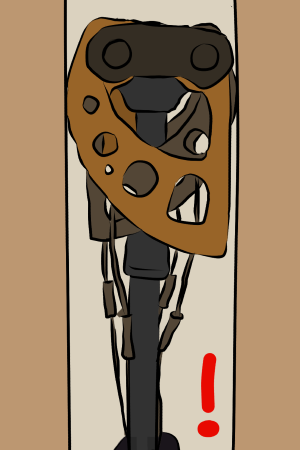

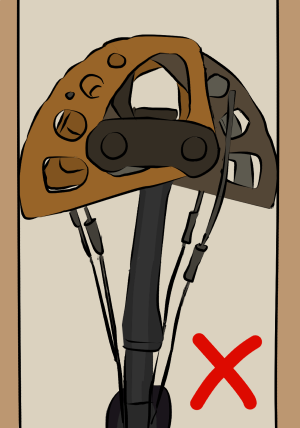

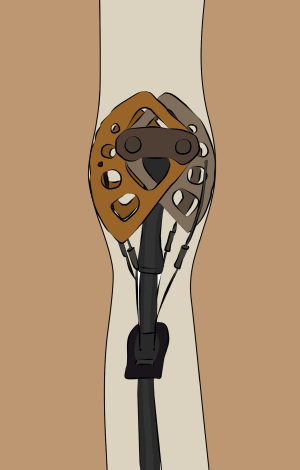

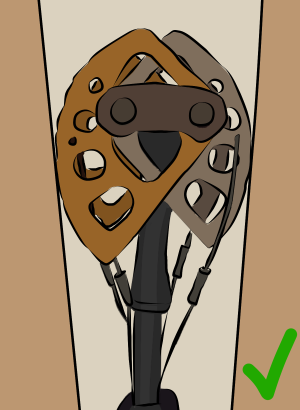

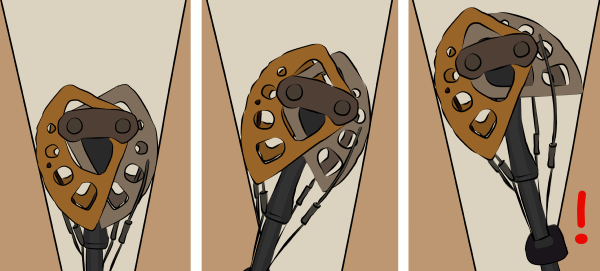

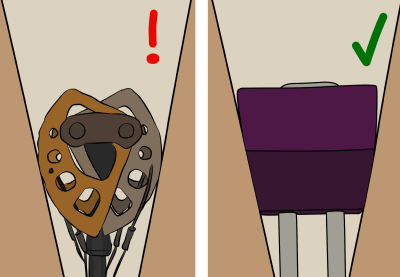

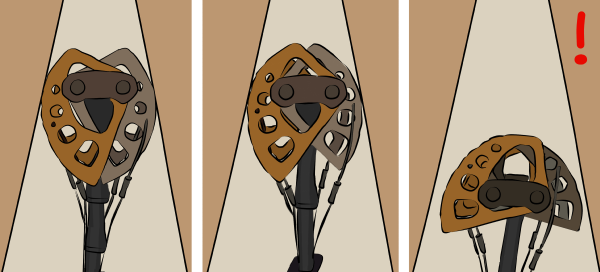

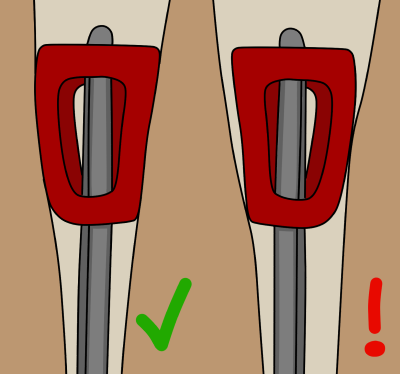

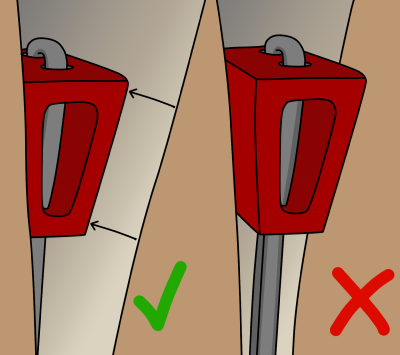

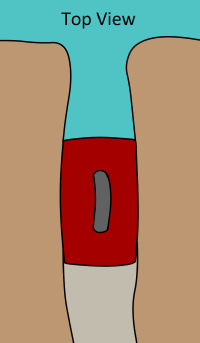

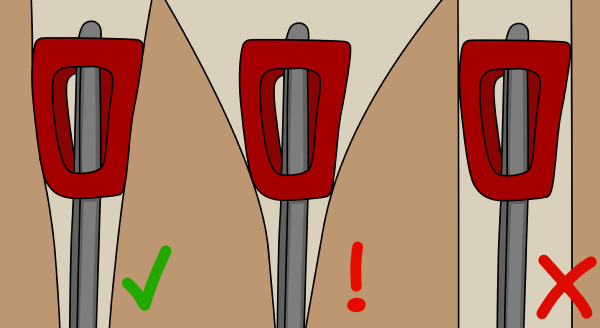

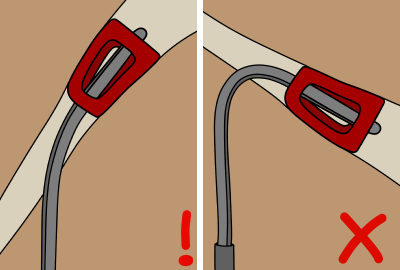

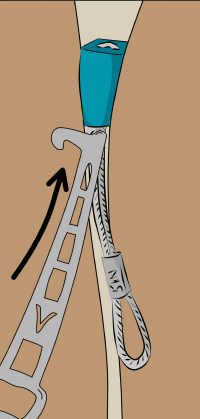

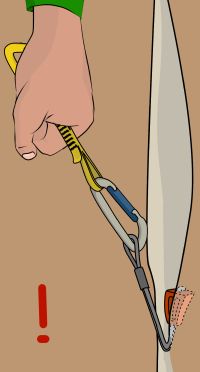

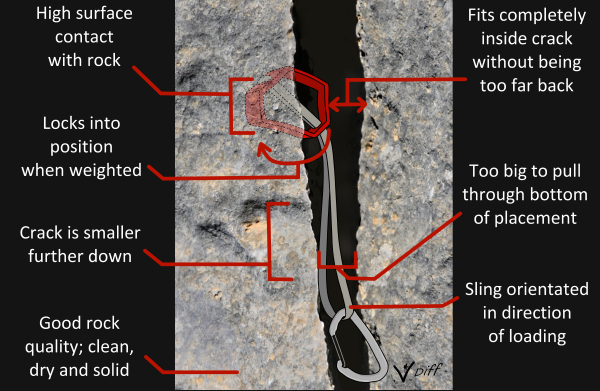

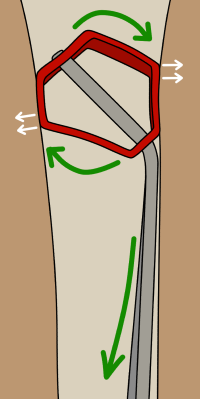

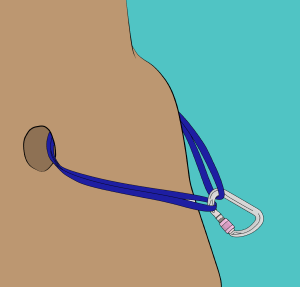

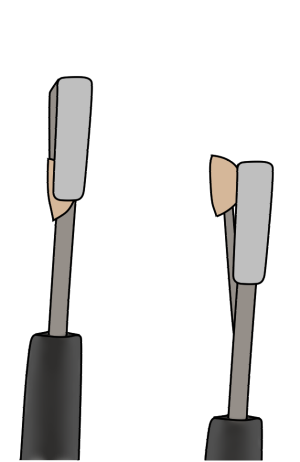

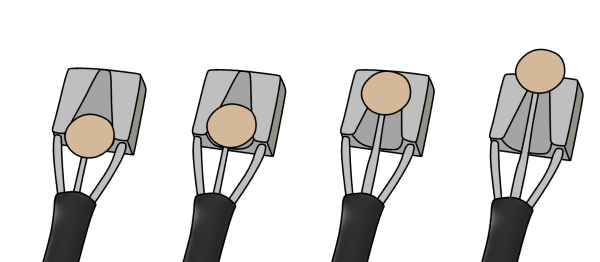

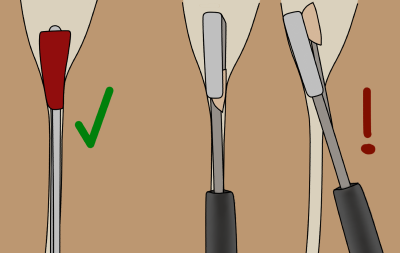

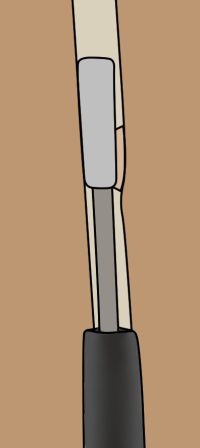

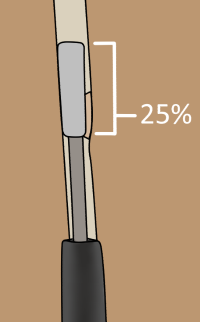

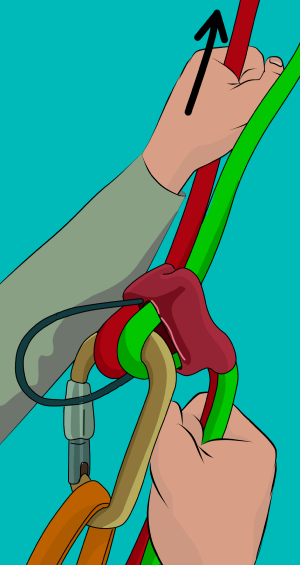

Assess each piece carefully; which way will it be pulled if you fall? How solid is the rock around the piece? Could it be pulled out by movement in the rope as you climb past? Could you remove it easily?

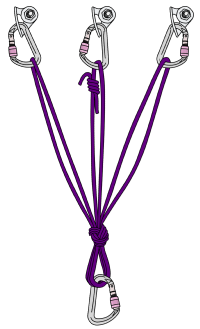

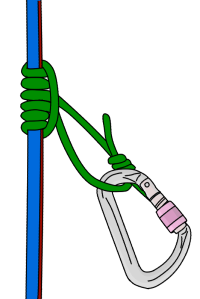

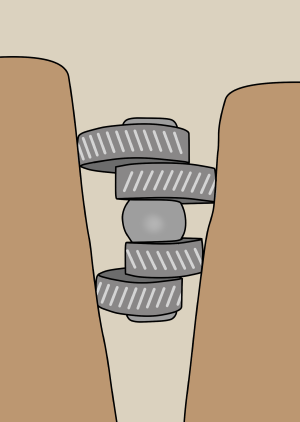

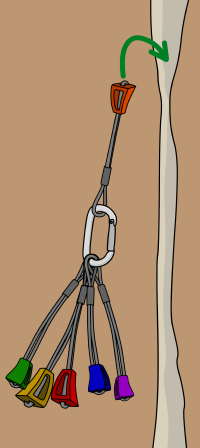

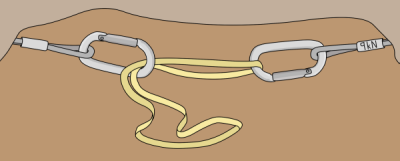

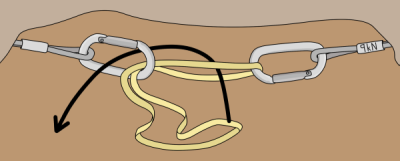

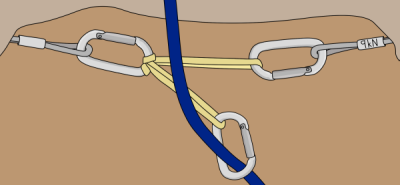

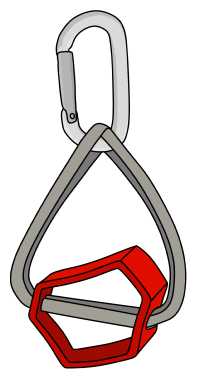

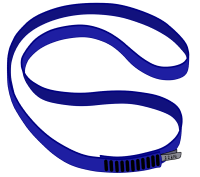

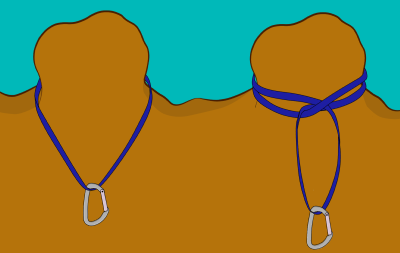

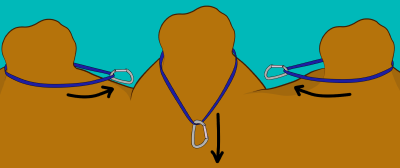

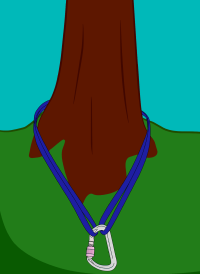

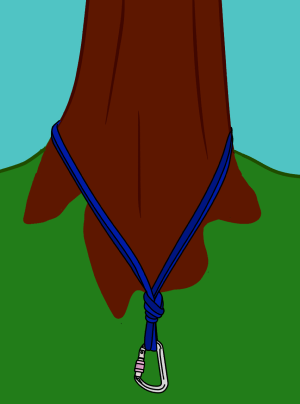

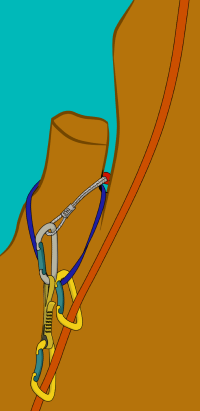

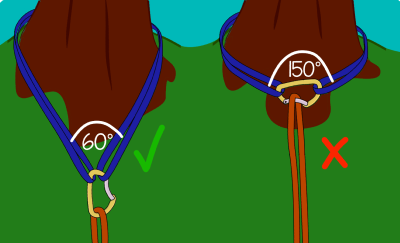

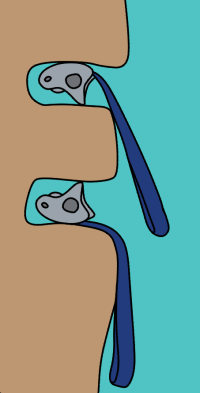

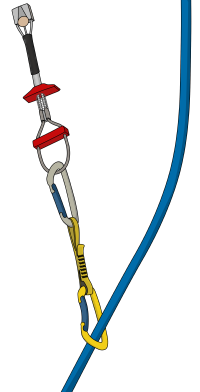

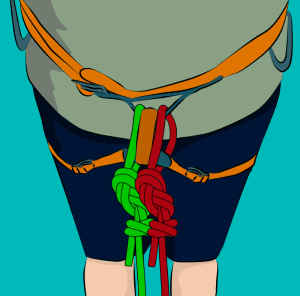

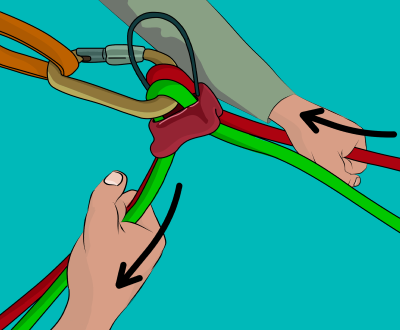

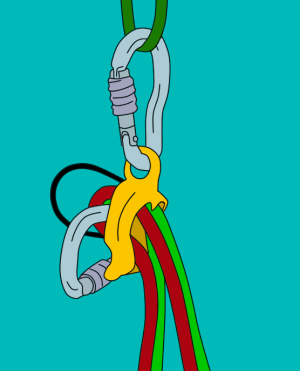

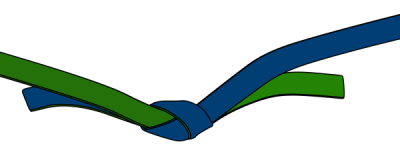

When you find a place which has three good pieces close together, practise equalizing them together with a cordelette or a long sling to make a belay. Have your experienced partner check the gear and give you critiques about whether it was placed correctly.

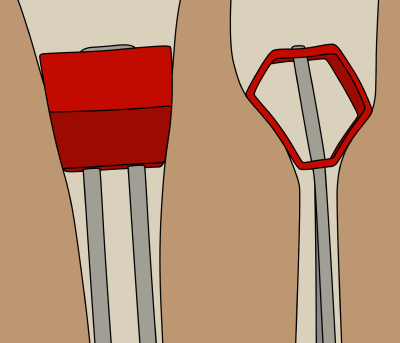

The fundamentals of placing gear are easy to learn. But recognising subtle constrictions in cracks and maximising rock-to-nut surface contact is an art only learnt through experience. Practise makes perfect!

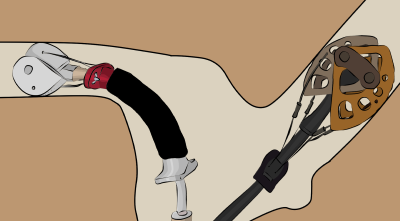

Follow the Leader

Once you've practised placing gear at ground level, the next logical step is to follow, or 'second', an experienced leader on a single pitch route. When you are removing the gear, try to understand how they placed it and why they chose that exact place instead of another. Remove each piece and then place it back in the exact same spot.

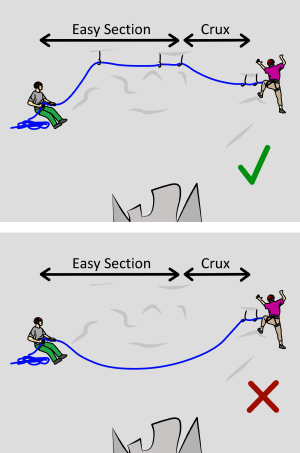

Lower Your Grade

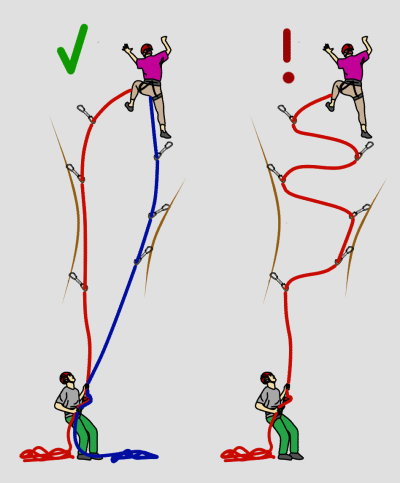

Choose a route that you find easy. A HVS trad route may equate to around F5+ on a grade conversion chart, but in reality it's much harder to climb the trad equivalent. While the actual moves are the same physical difficulty, it takes much longer to find potential gear placements, and to place gear well, than it does to clip a quickdraw. Also, without a line of bolts and coloured holds to follow, you'll often end up doing many more moves to reach the same point, and not always going the easiest way.

Take Your Time

Have a look around for better gear placements and take time to figure out the moves. Focus on placing each piece as perfectly as it can be. Make slow and controlled movements, committing to holds only when you've explored the best way of holding them.

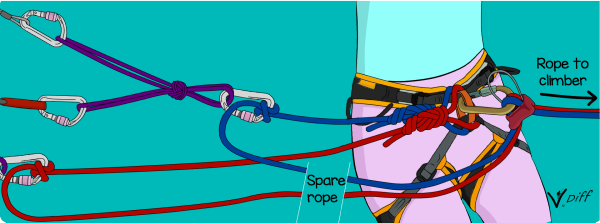

Make a Belay Plan

It's a good idea to assess the top of the crag first to find potential anchor points and figure out your belay position. Remember what gear you will need for the anchor and make sure to still have it when you reach the top!

Single Pitch

Try a short climb first. If something goes wrong, it'll be much easier to get down from a single pitch than a multi-pitch.

Be Ready

We strongly recommend that you take a course with a qualified climbing instructor. Once you have gained approval from them, you can lead your first climb. Wait until you're ready, but don't postpone it too long or you may never try. Be brave, take your time and focus on making the climb safe. And make sure to have fun!

Learning the techniques of placing gear and building anchors isn't enough to make you a proficient trad climber. Unexpected situations often arise, especially on multi-pitches (such as not having enough rope to reach a solid belay, or retreating from a climb with damaged ropes and poor anchors).

It's important to develop the ability to adapt your trad skills to suit situations like these that do not have a textbook solution. Being able to solve problems quickly is a vital skill which can only be learnt through experience.

So get out there, and climb some rocks!