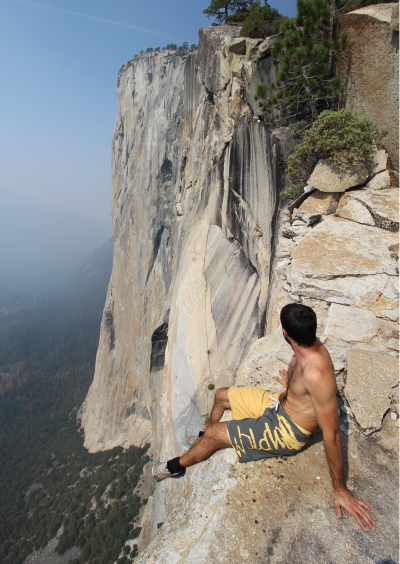

Standing on the summit of The Central Tower with my best friend was the greatest moment of my life.

Descending the tower was not.

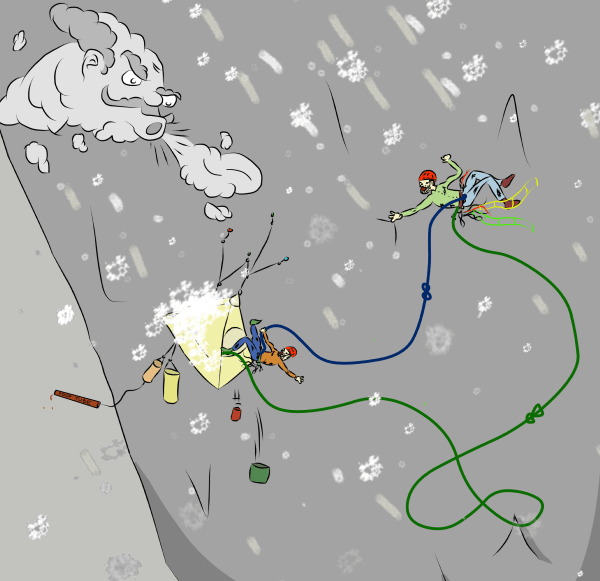

A brutal storm rolled in. We huddled inside the portaledge, waiting for an opportunity to descend.

After three days, we ran out of food and began descending anyway.

After about twenty rappels, but still with a few more to go, the air above us suddenly ripped into a deafening, scraping scream.

An enormous rock was falling towards us.

There was no escape.

The event itself seemed to unfold in a silent, slow-motion blur; outstretched arms were crumpled, granite blocks exploded, pieces of our belay were plucked out of the rock, pain was temporarily hidden by shock.

We survived, somehow.

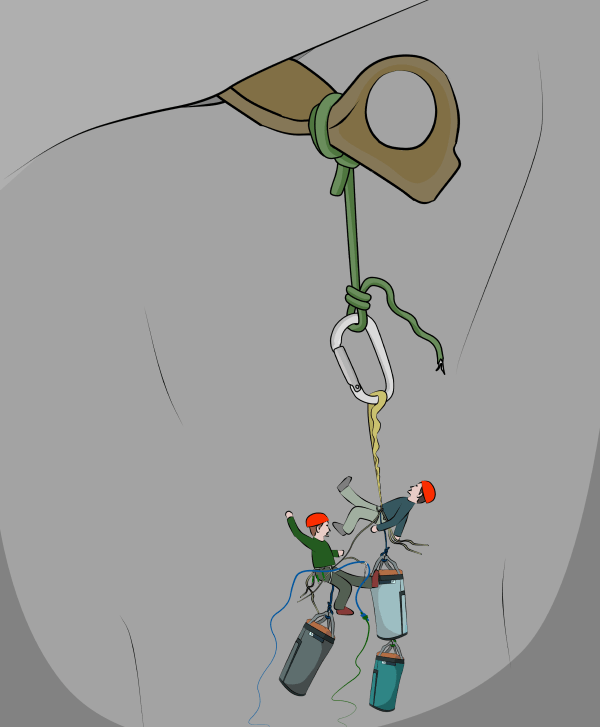

But then I saw the belay.

All of our haulbags, all of our equipment, my life and the life of my best friend were dangling solely from a single strand of frayed cord, the thickness and strength of a shoelace, which was wrapped around an ancient, rusty piton.

Our lives were literally hanging by a thread.

The adrenaline began to subside. Intense pain roared through my veins.

I tried to speak but the fuzzy onset of unconsciousness had frozen my voice into a hard lump of wordless desperation in my throat.

The rest of the descent is a distant blur in my memory. Always the strongest member of the team, Callum ensured we got down.

Back on the rubble-strewn ground, I untied from the rope and vowed to never climb again.

My memory deteriorated as the months passed by.

Time began to steal the details.

There are 3 characteristics that make a good big wall climber: A high tolerance of pain, a bad memory and ummm....

I forgot the other.